In the 1950s, popular characters were ones who were brave, moral, and examples of how to be an upstanding citizen. Jimmy Stewart, James Bond, Charlie Chaplin—these were the personalities of Hollywood’s Golden Age when the good guys always won. Indeed, the word “hero” comes from the Greek term for “defender” or “protector.” Heroes were typically mortal descendants of gods—something we see nowadays in the likes of Superman. But fast-forward to the 21st century and suddenly we’re met with a very different selection of “heroes.” Deadpool, Jack Sparrow, and Walter White are some of the most merchandised characters around, despite being (at least partly) the “bad guys.” Nowadays, audiences prefer compromised heroes. Viewers long for characters who are darker, grayer, and open to wider narrative possibilities that weren’t possible with heroic protagonists. Today’s protagonists can win many fans even without being brave, polite, or even likable. By lingering in that hazy crossover between hero and villain, today’s “anti-heroes” can make the most of both worlds, leading to new kinds of stories that are more realistic. Let’s take a deeper look at three of the best anti-heroes examples in cinema history, what makes them so compelling as characters, and how they set the stage for interesting stories.

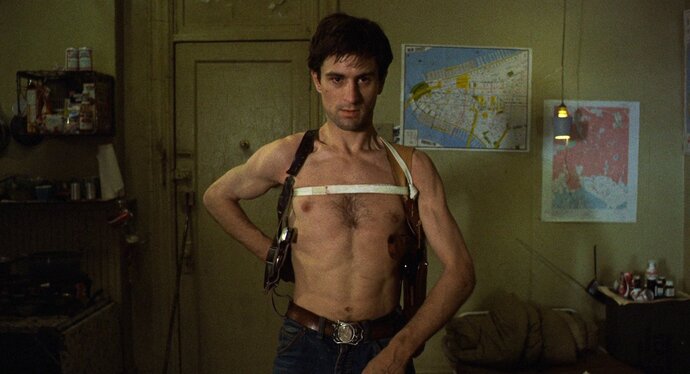

1. Travis Bickle (Taxi Driver)

Subject to intense psychological exploration, Taxi Driver is the movie that put director Martin Scorsese in the spotlight. Released in 1976, Taxi Driver follows Travis Bickle through the seedy streets of New York City as he drives around all night on account of his insomnia. We quickly learn that Travis Bickle is not your usual protagonist. He’s unsociable, depressed, and verging on being a stalker to the blonde and beautiful Betsy. Clearly dissatisfied with his life after the Vietnam War, he blames the woes of the world on the criminal “scum” of the streets—and takes it upon himself to wash them away. Despite his hatred of the illicit, he constantly surrounds himself with it. He takes a child prostitute under his wing and despises the trade, yet still attends adult theaters at night. He exercises and claims “you’re only as healthy as you feel,” yet pops pills and lives off junk food. Citing the Kris Kristofferson song “The Pilgrim: Chapter 33,” he overtly refers to himself as a “walking contradiction” who’s unable to stick to any moral code or belief system like a traditional hero would. A mentally unstable loner with a plot to kill isn’t exactly the archetype for a hero. So why is Travis Bickle one of the most famous and most compelling characters in cinema history? Well, Scorsese’s clear direction and talent for character development makes Taxi Driver a landmark film, regardless of whether the protagonist is good or bad. We witness his journey from disgruntled veteran to attempted assassin. And Travis doesn’t face an outright villain from the start; instead, we come to understand his motives from an introspective narration straight from his diary. After all, he’s a killer but he doesn’t kill just anybody—it’s the pimp and client to a 12-year-old prostitute who he yearns to set free.

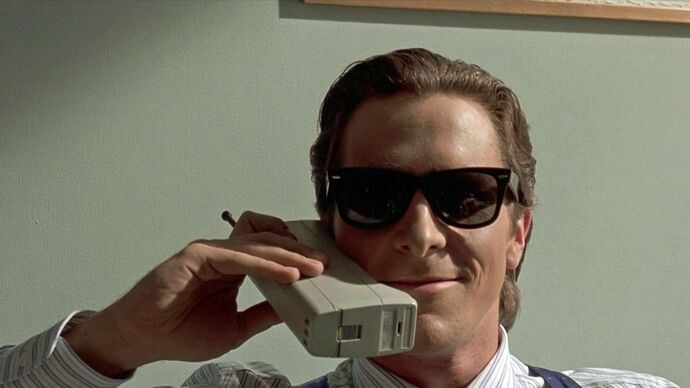

2. Patrick Bateman (American Psycho)

Patrick Bateman is a raving lunatic, brilliantly played by Christian Bale in American Psycho. Bateman narrowly manages to avoid being labeled a villain as the smooth-talking lead of Mary Harron’s dark comedy. Based on the 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis, American Psycho follows a New York yuppie who’s living a double life as both a businessman and a serial killer. A stereotype and metaphor for Wall Street materialism, Bateman boasts an extreme kind of vanity and neatness that borders obsessive-compulsive levels. In the opening scene, we see his near-religious morning routine of crunches and face scrubs. Later, we see Bateman physically sweating over a business card, and even later, focused entirely on his mirror reflection when having sex. All of this is done to poke fun at the hollow lifestyle of button-down businessmen in the 1980s, and it’s made even funnier by Bateman’s sarcastic and crude comments that are delivered with an eerie smile. Casually blurting out his bloody cravings mid-conversation is what makes Bateman an unusual (and interesting) character. His dark humor escalates and shocks us when he suddenly begins to murder people as if it’s the most normal thing in the world. His sociopathic smile puts us on edge, yet his wit and charm draw us in closer. Unlike a typical hero—who’d be emotionally torn between moral dilemmas—Bateman is devoid of emotion and empathy. (Or so he claims.) Yet there’s something contradictory in Bateman’s nature. For all his compulsive neatness and apparent lack of feelings, he’s prone to angry outbursts at the slightest inconvenience, and even cries down the phone in maniacal laughter when confessing his crimes. Like most anti-heroes, Bateman is likely suffering from mental illness—which we can see in how he approaches his health, appearance, apartment, career, and homicidal hobby—and that draws a tiny scrap of sympathy from us, the audience. Not only do we pity his inner torment, but we even find him admirable in his disgust toward all the capitalistic greed around him. We can’t help but laugh through Bateman’s iconic dance ritual when killing a co-worker, despite being a little horrified by it. He’s smart, stylish, and engaging to watch in a way that launches viewers through an emotional whirlwind that Superman could never achieve. You may not know how to react to this American psychopath, but you’ll never forget him.

3. Louis Bloom (Nightcrawler)

Played by Jake Gyllenhaal, Louis “Lou” Bloom in Nightcrawler is a fast-talking sociopath who’s willing to do anything that bangs him a buck. We first meet Lou as a thief, but he’s not an empty-headed lowlife. We witness his intellectual ability when he talks his way into a job. He’s quick with his words and able to manipulate almost anyone, including his boss (who he blackmails into bed). Creepy and wide-eyed, Lou lacks any sense of empathy for others and only cares about his own success. He takes advantage of his poor assistant Rick without thinking twice, and lies his way to the top of the ladder without so much as a flinch. But Lou isn’t a villain. In his blossoming career as a stringer who captures violent and disturbing footage to sell to news stations, he never actually kills anyone. He simply films people who are suffering and/or dying. He’s opportunistic and slimy and heartless, but he’s not malicious. Dan Gilroy’s thriller is a social commentary about the damaging effects that result when tragedy is exploited and broadcasted on TV to shock (and even entertain) viewers. Although Lou is certainly to blame for his immoral priorities, so the blame also rests on the news industry that encourages and rewards Lou for capturing such gruesome footage. “If it bleeds, it leads” is a real term used in the corporate world, which Lou takes to the extreme when he follows a potential criminal in hopes of witnessing a crime rather than preventing it. There are aspects of Lou that audiences can’t help but be intrigued by. He’s so unusual in his empathy-empty ways that we’re curious to know more about this almost-alien protagonist. He’s handsome, brave, and committed to working hard—traits shared by most traditional heroes. But he’s full of contradictions! He’s compulsively neat, yet thrives in messy crime scenes. He’s emotionless, but rage and desperation bubble under the surface. This complexity makes him a more developed character that’s wholly unpredictable, and that’s what makes him compelling. Nightcrawler is stylistic and carefully woven together, lit under shadowy neon lights as Lou films under the cover of darkness. Intrigued by his manipulative genius and ability to stay collected under immense pressure, we try and understand his motives.